Despite the usual pushback from the medical profession, the work of Dr. Albert Abrams -- which was discussed in an earlier post in this sequence -- attracted a great deal of attention from medical practitioners who were willing to push the envelope. That allowed Abrams' work to come to the attention of the next pioneer of radionics, Dr. Ruth Drown. (That's her on the left.) Drown entered the medical profession the hard way. Born in rural Colorado in 1891, she married a local farmer, but caught a train to Los Angeles in 1918 with her children to escape domestic abuse. She landed on her feet, worked in a variety of jobs, and in 1923 became a nurse working for Dr. Frederick Strong, one of a number of physicians who used Abrams' equipment to diagnose and treat patients. She turned out to have a remarkable talent for healing with the Abrams method. Her experiences and succesful cures convinced her to study for a chiropractic degree, which she earned in 1927.

Despite the usual pushback from the medical profession, the work of Dr. Albert Abrams -- which was discussed in an earlier post in this sequence -- attracted a great deal of attention from medical practitioners who were willing to push the envelope. That allowed Abrams' work to come to the attention of the next pioneer of radionics, Dr. Ruth Drown. (That's her on the left.) Drown entered the medical profession the hard way. Born in rural Colorado in 1891, she married a local farmer, but caught a train to Los Angeles in 1918 with her children to escape domestic abuse. She landed on her feet, worked in a variety of jobs, and in 1923 became a nurse working for Dr. Frederick Strong, one of a number of physicians who used Abrams' equipment to diagnose and treat patients. She turned out to have a remarkable talent for healing with the Abrams method. Her experiences and succesful cures convinced her to study for a chiropractic degree, which she earned in 1927. As soon as she hung out her shingle and began practice, she began experimenting with modifications on Abrams machines. She was apparently the first person to guess that the effects Abrams and his peers were getting had nothing to do with radio waves or electricity, and began to devise machines of her own that had electrical wiring but used no electrical current. Her talent for naming devices, alas, was not on a par with her talent for healing; she called her most successful device the Homo-Vibra Ray. (In her defense, "homo" as slang for homosexual wasn't yet in common use. George Winslow Plummer's once-famous volume Rosicrucian Fundamentals, published in 1920, began with the ringing sentence: "The subject of Rosicrucianism is Man, the Homo.")

Some of her innovations turned out to be crucial for the evolution of radionics -- a term which she invented, by the way. Along with the recognition that some force distinct from radio waves and electricity was responsible for radionics cures, she pioneered the "stick pad," a plate of glass or plexiglass used by radionics machine operators to gauge the flow of the unknown force through the machine, and she began the systematic collection of "rates" -- settings on radionics machines -- which are specific to illnesses, organs, and other factors. These became standard elements of radionics during her lifetime and remain common today.

Some of her innovations turned out to be crucial for the evolution of radionics -- a term which she invented, by the way. Along with the recognition that some force distinct from radio waves and electricity was responsible for radionics cures, she pioneered the "stick pad," a plate of glass or plexiglass used by radionics machine operators to gauge the flow of the unknown force through the machine, and she began the systematic collection of "rates" -- settings on radionics machines -- which are specific to illnesses, organs, and other factors. These became standard elements of radionics during her lifetime and remain common today. Some of her other claims pushed the boundaries of radionics further than many subsequent practitioners have been willing to go, and helped fuel the debunking crusade against her. She found, according to her writings, that she could get accurate readings using a drop of blood from the patient, and that she could treat patients at a distance using the same medium. (Paracelsus, the great Renaissance alchemist and physician, made the same claim; both were able to produce evidence for it.) The spookiest of her achievements, and the one that came in for the most criticism, was the apparent ability of her Radio-Vision machine to take photographs of organs at a distance -- photographs that apparently showed lesions where medical diagnosis by other means found them to be. The judge, predictably, refused to let these be introduced as evidence in her trial.

Yes, there was a trial. In the wake of the Second World War, as the American Medical Association and the pharmaceutical industry tightened their grip on health and healing in the United States, alternative medical practitioners of all kinds came in for increasing persecution under laws designed to defend the medical monopoly. In 1950, at the behest of the AMA, federal authorities brought charges against Drown. Most of the evidence she offered in her own defense -- evidence that her methods worked, and that she had successfully diagnosed and treated thousands of patients -- was excluded from her trial. She was accordingly convicted of interstate fraud for shipping one of her machines across a state line and served a brief prison sentence. Still more legal charges were pending against her when she died in 1965.

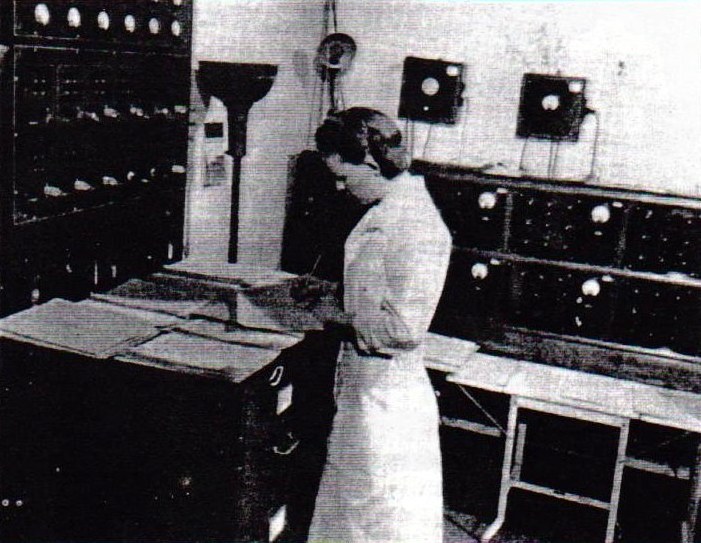

Yes, there was a trial. In the wake of the Second World War, as the American Medical Association and the pharmaceutical industry tightened their grip on health and healing in the United States, alternative medical practitioners of all kinds came in for increasing persecution under laws designed to defend the medical monopoly. In 1950, at the behest of the AMA, federal authorities brought charges against Drown. Most of the evidence she offered in her own defense -- evidence that her methods worked, and that she had successfully diagnosed and treated thousands of patients -- was excluded from her trial. She was accordingly convicted of interstate fraud for shipping one of her machines across a state line and served a brief prison sentence. Still more legal charges were pending against her when she died in 1965. Some of her equipment survived, and inspired other students of radionics -- the device above is one example. After her time, however, while radionics flourished elsewhere, it was forced underground by legal proscription in the United States. The fate of the next pioneer of etheric healing we'll be discussing put the seal on that process. The golden summer of etheric medicine was ending, and a bitter winter followed.